Julius Hatofsky

Obituary

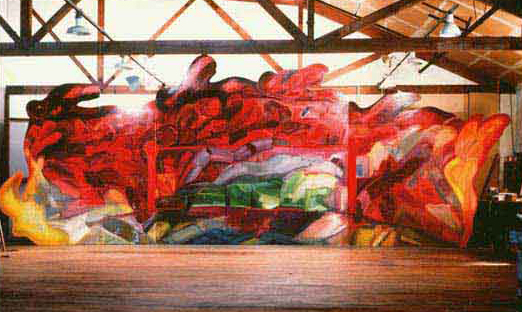

(Above: Installation view, San Francisco loft - click image to view painting)

Marianne Costantinou Chronicle Staff Writer

Pub Date: Sunday 1/22/2006

Until his death earlier this month, Julius Hatofsky may have been one of the greatest living artists that nobody ever heard of.

Mr. Hatofsky, an Abstract Expressionist and a longtime instructor at the San Francisco Art Institute, died at the age of 83 without ever gaining popular recognition of his immense talent. "I had long thought Hatofsky one of the most unjustly neglected painters on the American art scene,'' wrote Hilton Kramer, the prominent and difficult-to-please art critic, in a 1994 New York Observer review of an exhibit. "But now suddenly I realized he was a real master whose work almost nobody knows."

It was partly by choice. He refused, said those close to him, to kowtow to the fickle trends dictated by art critics, museum curators, gallery owners, dealers and housewives needing something for the wall to go with the couch.

"He was totally incapable of any kind of self-promotion,'' Kramer said in a phone interview.

"Had he sought publicity, he would have been one of the canons of the art world, the kind you see in art history books,'' said Susan Hillhouse, chief curator of the Triton Museum of Art in Santa Clara, where he had his last show. "He was more interested in art-making than art-marketing."

Mr. Hatofsky not only didn't chase the limelight or the easy buck, but he turned down offers from museums and galleries that he felt wouldn't justly represent his work, said Hillhouse.

"Julius was very much his own person,'' said his second wife, Linda, his companion for more than 30 years. "When he was supposed to say 'yes,' the word 'no' always came out of his mouth."

Hillhouse felt pessimistic when she approached him last year to invite him to exhibit. To her surprise, he said yes. The show, his first in a decade, coincidentally closed on Jan. 1, the day of his death after a long battle with cancer.

Inspired largely by William Blake -- the 18th-century poet, painter and engraver whose artwork was also unappreciated during his lifetime -- Mr. Hatofsky's oil paintings are notable for their rich color palette and an internal structure contrary to the improvisational style of contemporary abstract painters. The size of his canvas was also remarkable, with several 12 feet by 30 feet.

Mr. Hatofsky's art, Kramer wrote, "resembled that of no other living artist."

Though Mr. Hatofsky's vast oil canvases were unique, his is also the classic story of the struggling artist.

"There are many, many accomplished artists who you never hear about," Kramer said.

Who "makes it" in the competitive art world is often more luck than talent.

"It's a roll of the dice,'' he said. "A lot depends on fate: who you meet, if the media happens to notice you ...."

Which is not to say that Mr. Hatofsky died in anonymity, a neglected Vincent van Gogh tucked away in his home in Vallejo.

For 33 years, Mr. Hatofsky taught painting and figure drawing to generations of aspiring artists at the San Francisco Art Institute. He befriended many, treating them to a round of drinks and a good cigar at the pub, and inviting hundreds at a time to standing-room-only parties at his 5,600-square-foot SoMa loft. He rented the loft for decades, until the dot-com boom of the mid-1990s pushed him and his wife to a Victorian house in remote Vallejo, the nearest town to San Francisco where he could afford to buy a house.

"He was like a friend who was a teacher,'' said Philip Govedare, a student of his in the late 1970s who is now an associate art professor at the University of Washington in Seattle. "He had a real big following with students. They could feel he was the real thing.''

Tall, handsome, modest and soft-spoken, Mr. Hatofsky exuded a quiet charisma and kindness that made him a magnet for students, said a former colleague, Bruce McGaw, who has known him since the mid-1960s. When Mr. Hatofsky retired in 1995, alumni contributed $20,000 to publish a catalog of his work. And dozens flew in from across the country to see the show at the Triton, gushing to Hillhouse what an inspiration he had been to them.

"He imparted a real passion about art, a vision about the magic that can come out of something you create,'' Govedare said.

Though unwilling to play the politics and make the compromises required to make it in the art world, Mr. Hatofsky was not such a saint that he didn't resent the sight of mediocre paintings hanging in museums or a hack's work selling out at galleries, said Bill Scharf, an artist and close friend for more than 50 years.

"There's an awful lot of awful art around,'' Scharf said. "We had a lot of good times laughing'' at it.

"I guess the choice could have been made to make a lot of money,'' he said. "It's a different kind of caring ... . Jerry and I wanted vitality and beautiful color and strength in a painting. That's different than what a gallery dealer would think is salable."

ack in the 1950s when Scharf and he met, Mr. Hatofsky went by the first name Jerry, a nickname given to him by his aunt because he was so industrious, a "Jerry on the job," said his wife. At the time, Scharf and Mr. Hatofsky were in New York City just starting their careers but working for food and rent as museum security guards, Scharf at the Museum of Modern Art and Mr. Hatofsky at the Whitney, then located next door on 54th Street. It was one of many odd jobs Mr. Hatofsky had since graduating from high school and giving up a college scholarship to work to support his family.

He was born on April Fool's Day 1922 in the upstate New York town of Ellenville and grew up in the historic Astoria neighborhood in Queens. His dad died when he was a child, so his mother took in sewing to support the three children.

After high school, Mr. Hatofsky worked on the docks and sold men's socks at Saks for several years before enlisting at age 20 in the Army to fight in World War II. A foot soldier later promoted to sergeant, Mr. Hatofsky was part of the 82nd Airborne Division, landing by glider behind enemy lines in the invasion of Normandy, and fighting in the Battle of the Bulge.

Upon returning to New York, Mr. Hatofsky enrolled as a student at the Art Students League, attending classes during the day while working nights as a police officer until his graduation in 1950. As an officer, he told Scharf, he never wrote a ticket, never cuffed anyone and never drew his gun.

Though he didn't get the attention he deserved in life, Scharf said, his commitment to his art never wavered.

"He was not rich or famous,'' said his friend. "But he was successful because his art is going to live on."

In addition to his wife, he is survived by his younger brother, Jack Hadley of Los Angeles.

A memorial gathering is planned for March 4, from 4 p.m. to 9 p.m., at Sweetie's Art Bar, 475 Francisco St., San Francisco.