Julius Hatofsky: The Unknown Studio

by Linda Hatofsky

Cadmium Red, Viridian Green, Burnt Umber, Cerulean Blue -- As I wander through the rooms of my home, I'm enveloped by these extravagant sounding colors restlessly moving within turbulent sensual images. They inhabit the abstract paintings of my late husband, Julius Hatofsky. And wood-- I'm surrounded by wood--- not only from the original oak floors of this 105 year old Victorian where he lived the last six year of his life, but lignum vitae, curly maple, African padauk, Purpleheart--- exotic woods with which he constructed unique, one of a kind inlaid tables carved with images of nature and human figures-- his hobby, he used to say. He died at 83 of complications from cancer during a rain storm at 3:59 AM on New Year's day, 2006. When I returned home alone from the hospital, the images in the paintings seemed to float in space, bobbing and swirling as I viewed them from my glass of wine, sobbing. He wanted to die in the midst of these paintings and I had arranged with hospice for that to happen. Regretfully, our doctor informed me that he could die in the ambulance and would not even know where he was if he made the trip home.

Admirers of Julius' work call him "the real thing", a painter who lived to paint. Our relationship endured thirty three years and, in truth, Julius painted every single day until the cancer weakened him in 1999. In fact, when we first spent a night together, he gently asked me if I would mind leaving early in the morning because the light was perfect then and it was his favorite time to paint. During the following years, he became used to my presence and I often watched him attack a huge white canvas as if he were forging ferocious winds of color into an invisible landscape.

For many years, we traveled to various cities in Europe for three weeks at the end of each year. We chose cities-- London, Paris, Madrid, Venice, Florence, Barcelona-- because of the paintings he wanted to visit again and again. He would carry a cigar box in his suitcase full of colored pencils and 5"X 9" cards. After we'd visit the Blakes in London, Tintorettos in Venice or Goyas in Madrid, he would return to our hotel room and draw his favorite images of that day on the cards with the pencils. These were studies for larger paintings, but also tiny compositions themselves. When he died, he left me with thousands of pieces of work-- oil, acrylic, charcoal, mixed media-- from 5"X 9" pencil drawings to 12'X 30' oil paintings.

Julius saw his first nude at sixteen when an older friend took him to a W.P.A. Art class. He graduated from high school with a scholarship to the Art Students League in New York City, but was unable to accept the honor; he needed to find work to support his family. Born in Ellenville, New York in 1922 to Russian Jewish parents, he watched his mother struggle for years doing piece-work and sewing to feed three children after his father died when he was two.

In 1942, Julius was drafted into World War II and distinguished himself as a foot soldier and a member of the 82nd airborne. He carried a mortar base plate on his back on the ground and as he watched his fellow soldiers fall away from him in combat, he vowed that if he survived, he would become a painter, but a painter on"his own terms". He entered three decisive battles by glider in the war: The Battle of the Bulge, the Holland invasion and Normandy, later liberating a concentration camp. The harrowing experience of his wartime duty influenced his painting and his life. After the war, he used the G.I. bill to attend the Arts Students League and the Hans Hoffman School in New York and traveled to Paris to study at The Grand Chaumiere. He supported himself in New York as a carpenter, selling socks at Saks Fifth Avenue, and doing a stint as a traffic cop even though he never drove a car.

He gained a certain amount of notoriety as a young painter, creating the first painter's loft in Hoboken, New Jersey, and being voted one of the ten most promising artists in New York. He was categorized as an emerging abstract expressionist and was included in the Whitney Annual of "New Talent" in 1959. He exhibited at the Avant-Garde Gallery, the then prestigious Charles Egan Gallery, both in New York City, and the Holland-Goldowsky Gallery in Chicago. In a review of an exhibition in 1957 at the Avant-Garde Gallery, the reviewer in Arts Magazine writes, "Vast, infinitely extending spaces are opened up before the observer in Hatofsky's canvasses which are so large that one is engulfed by their very magnitude. Passages of beautiful painting crowd upon one another as the pigment is laid on with a richly luxuriant feeling for color and texture."

In the early sixties, the break-up of his first marriage and a growing feeling of unease with the New York art scene prompted him to travel to San Francisco where he accepted a job at the San Francisco Art Institute as a Painting and Drawing instructor. For three decades, Julius nurtured, inspired and influenced countless students with his patience and quiet sense of humor. And even though his classes were always full, he'd continually allow new students to attend or work at home and meet with him periodically. Because of his extreme shyness, he never lectured or spoke in front of his classes but preferred to work with each student individually.

Beginning in the seventies at the end of each school year, we would host a huge party for students, teachers, and friends. A week before, we'd write invitations on 3"X 5" cards which he would distribute because he could not verbally announce the gathering to his classes. When he retired in 1995, his students, past and present, amassed $20,000.00 in order to create a catalogue of his work.

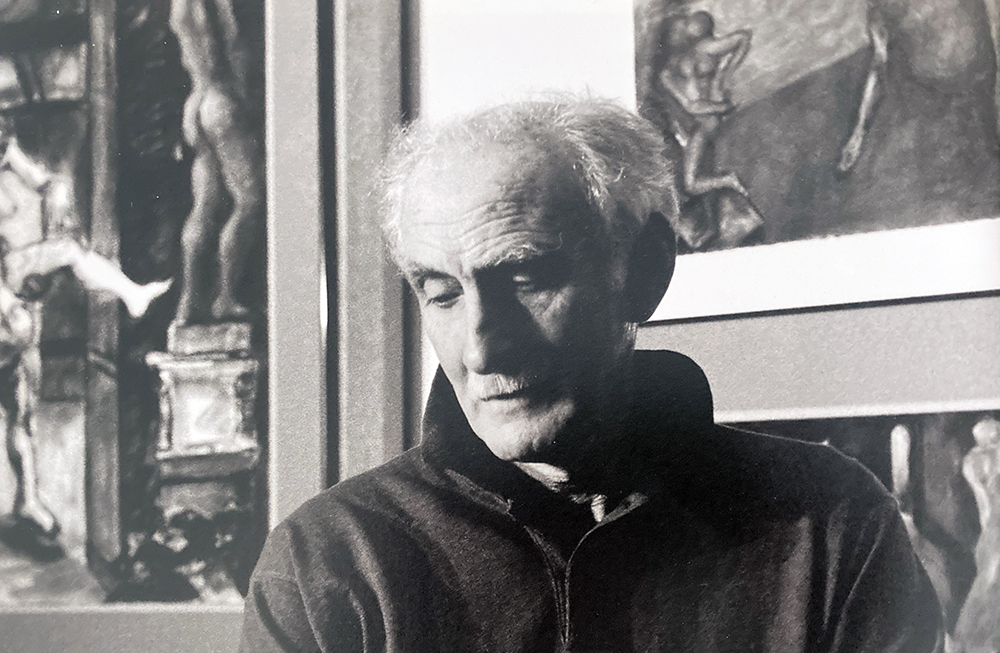

In 1971, Julius moved to a 5600 square foot loft south of Market Street in San Francisco where he crafted a superb studio and living space and continued his exploration of abstraction, working on some paintings for as long as twenty years, the largest two being 12' X 30'. He painted canvasses of all sizes using oils and acrylics, drew the figure often in a somewhat whimsical manner, and fashioned his unique tables "laboring at a great distance from the limelight in order to pursue and perfect the vision that haunts... whether or not the work conforms to the fashions of the moment."(1) I met him in 1972 and moved into the loft two years later. I first saw him at a New Year's Eve gathering. He was standing behind the hostess when she opened her door and I determined that his face was one of the most beautiful I had ever seen-- sensual, sensitive and kind. He was tall, slim and muscular-- an avid tennis player-- a man whose balding grey, silver hair and mustache added to his handsomeness.

Over the years, he was often shunned by the San Francisco art establishment, overlooked for large exhibitions of California painters at the museums. The critics and curators debated: Was he a New York or San Francisco painter? How could his paintings be categorized? He was made to feel as if he didn't belong to any movement and became resigned to the slights and petty power games of those engrossed in the machinations of the highly competitive art world.

And his paintings WERE hard to categorize. They were rich with his own inner vision and visual vocabulary, so much so that they were often labeled "inaccessible". To complicate matters, he was stubborn, mercurial, temperamental, and often quick to refuse offers of help. He'd say, " When I was supposed to say 'yes', I heard myself say 'no'". He remained "difficult" because he refused to conform to the dictates and habits of a world dominated by money and fashion; he insisted on following his own vision. In 1993, Hilton Kramer, art critic and publisher, visited the loft when Julius exhibited in two solo shows concurrently. He later wrote in an article in "Art and Antiques", "The bulk of the paintings in both the Monterey and San Jose exhibitions were drawn from the last twenty years or so, yet they represent only a small part of what Hatofsky has created in this period. Visiting his capacious studio these days, you have even more of a sense of what his copious production has encompassed though his recent exhibitions were large and well selected. On most days of the year, in fact, the Hatofsky studio is the best show in town, even though most of the city's dealers, curators, critics, and collectors are scarcely aware of its existence."

Even though he remained relatively unrecognized except for loyal admirers, he received awards and grants acknowledging his abilities and perseverance. At one award ceremony, a dinner honoring six outstanding artists at the Guggenheim Museum in 1987, he was expected to accept the honor with a short speech. When he reached the podium after being given a glowing introduction, he was barely able to utter the words "Thank you", so devastating was his shyness. Julius, a man who loved the rituals surrounding food and drink, suffered throughout the elaborate dinner until his moment of torture was over.

Perhaps because of his shyness, he distrusted words. He was reticent to talk about his work and when asked about its meaning often scratched his head and laughed, saying "Sometimes I don't know what I'm doing."He gave titles to some of his paintings, but disliked doing so because he felt the words limited the scope of possibilities, demeaned the imagination. He wanted people to feel when they looked at the work. When someone would stab at the meaning of a certain image, he'd smile and say, "That sounds good." Towards the end of his life, he did a series called "Departing Spirits" in response to friends who had recently died. He started using figures in his paintings and near his death, body parts, fashioning them within abstract forms calling them "Dream Fragments". He painted a number of somewhat humorous charcoal acrylics entitled, "The Unknown Studio" in which a sculptor labored determinedly, surrounded by numerous female sculptures and a nude. The idea might have come from his feelings of anonymity but also from the word "UNKNOWNS" written one day in crayon outside our very undefined door to the loft. He considered it an omen.

Frequently, he and other painters would hire a model and draw the figure in the loft because it was so large. After drawing the model, he would surround her with other nude figures often in erotic poses, but always with whimsical humor. One day, a tour from the Museum of Modern Art descended on the loft and a woman was so incensed by twenty or so of these 22" X 30" charcoal acrylics hanging on a wall, she asked him, "Why don't you paint flowers?" Angrily accusing him of degrading women, she stomped out after he asked her to leave. Later, he joked, "At least she felt something."

His distrust of words did not extend to books. He read voraciously, often historic non-fiction, especially about World War II. Because of his participation in the war and liberation of a concentration camp, he read endless fiction and personal accounts of the battles. He never spoke of the concentration camp except to say that he would always remember the smell. One night we were watching television and a paraplegic from the war was being interviewed. I happened to look at Julius and tears were streaming down his face. He merely uttered, "Brings back memories". He read all of Solzenitism, struggled through Grossman's "Life and Fate", a sweeping account of the siege of Stalingrad, and marveled at the writings of Rysard Kapuscinski who witnessed 27 revolutions in the third world. I often joked about his "light" reading material, although he did enjoy A.J. Liebling for a little comic relief.

Art critics were not always kind to Julius and opinions expressed in reviews written early in a painters' career often stick with them. Writings about him in New York in the fifties and sixties described the paintings as "surging" "turbulent" "densely alive" "undulating". In a review of a show in 1959 at the Holland-Goldowsky gallery in Chicago, he was described as "a painter deliberately set against the main stream, whose work, while it owes some debt to the New York school, is fundamentally divergent from it." The idea of "against the main stream" stuck and a one-man- show at the Monterey Museum in 1993 was entitled "Julius Hatofsky Against the Grain."

But the most common criticism dealt with the "withheld meaning" of his paintings. In a review of a show exhibiting his "Dark Columns" series at the Paule Anglim gallery in San Francisco in 1985, Linda Aldrich wrote, "Because their (the paintings) central tensions and resolutions are private to Hatofsky, the paintings in the last analysis, promise more than they deliver. I find this lack of communication disappointing. Hatofsky is too strong a painter to cloister himself in a private visionary cell."

But Rick Deragon reviewing the Monterey Museum show saw differently:

"Organic forms thrust, clash and dematerialize in dramatic compositions, and colors appear to melt and burn in ethereal landscapes... The upward eruptions of form that give way to crescendos of fleeting shapes, suggest great themes --- origin, eternity, eruption, time and passage... Hatofsky's painting has evolved outside the mainstream over the years, for his abstract painterly style has run its own personal course since the late 1950's."

Julius' last exhibition at the Triton museum in San Jose, California closed the day he died. Mark van Proyen wrote a review of the show that appeared in Art in America. He was especially taken with the "stupendous irregularly shaped three-panel work measuring 10 by 33 feet (Untitled, 1968-89) which the artist repeatedly returned to for more than two decades. In it we see several groups of figures struggling to extricate themselves from dark recesses, as if to ascend a symbolic mountain of ebullient, glistening color at the center of the epic composition. A compendium of the artist's style and imagery--a kind of Achilles shield offering a vision of what life is and should be--it is an engagingly complex work with a totemic feel."

Julius' answer to the divergent critical opinions of his work and the contrivances of the art world was written on a simple white card pinned near the telephone in the loft: "Shit is flying and critics are rushing to pick-up the flak." And he would always return to the work: "Every time I'm slighted, it makes me angry and I work harder."

A friend once asked him if he had any regrets in his life and his answer was consistent with his actions. "I would have liked to make a little more money on the paintings, but I've done what I want in my life and, in some ways, I'm grateful I've been left alone."

Writing in The New York Observer on January 31, 1994, Hilton Kramer commented, "I had long thought Mr. Hatofsky one of the most unjustly neglected painters on the American art scene, but now, suddenly, I realized that he was a real master-- an American master whose work almost nobody knows."

Linda Spector Hatofsky

Vallejo, CA

Winter 2011

--------------------------------------------

1- Kramer, Hilton "Out of the Limelight", Art and Antiques, March, 1994.